Emily Wilding Davison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English

Emily Wilding Davison was born at Roxburgh House, Greenwich, in south-east London on 11 October 1872. Her parents were Charles Davison, a retired merchant, and Margaret ' Caisley, both of

Emily Wilding Davison was born at Roxburgh House, Greenwich, in south-east London on 11 October 1872. Her parents were Charles Davison, a retired merchant, and Margaret ' Caisley, both of

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

who fought for votes for women

A vote is a formal method of choosing in an election.

Vote(s) or The Vote may also refer to:

Music

*''V.O.T.E.'', an album by Chris Stamey and Yo La Tengo, 2004

*"Vote", a song by the Submarines from ''Declare a New State!'', 2006

Television

* " ...

in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

(WSPU) and a militant fighter for her cause, she was arrested on nine occasions, went on hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

seven times and was force-fed

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into t ...

on forty-nine occasions. She died after being hit by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

's horse Anmer at the 1913 Derby when she walked onto the track during the race.

Davison grew up in a middle-class family, and studied at Royal Holloway College

Royal Holloway, University of London (RHUL), formally incorporated as Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, is a public research university and a constituent college of the federal University of London. It has six schools, 21 academic departm ...

, London, and St Hugh's College, Oxford

St Hugh's College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford. It is located on a site on St Margaret's Road, to the north of the city centre. It was founded in 1886 by Elizabeth Wordsworth as a women's college, and accepte ...

, before taking jobs as a teacher and governess. She joined the WSPU in November 1906 and became an officer of the organisation and a chief steward during marches. She soon became known in the organisation for her militant action; her tactics included breaking windows, throwing stones, setting fire to postboxes, planting bombs and, on three occasions, hiding overnight in the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

—including on the night of the 1911 census. Her funeral on 14 June 1913 was organised by the WSPU. A procession of 5,000 suffragettes and their supporters accompanied her coffin and 50,000 people lined the route through London; her coffin was then taken by train to the family plot in Morpeth, Northumberland

Morpeth is a historic market town in Northumberland, North East England, lying on the River Wansbeck. Nearby towns include Ashington, Northumberland, Ashington and Bedlington, Northumberland, Bedlington. In the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 ...

.

Davison was a staunch feminist and passionate Christian, and considered that socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

was a moral and political force for good. Much of her life has been interpreted through the manner of her death. She gave no prior explanation for what she planned to do at the Derby and the uncertainty of her motives and intentions has affected how she has been judged by history. Several theories have been put forward, including accident, suicide, or an attempt to pin a suffragette banner to the king's horse.

Biography

Early life and education

Emily Wilding Davison was born at Roxburgh House, Greenwich, in south-east London on 11 October 1872. Her parents were Charles Davison, a retired merchant, and Margaret ' Caisley, both of

Emily Wilding Davison was born at Roxburgh House, Greenwich, in south-east London on 11 October 1872. Her parents were Charles Davison, a retired merchant, and Margaret ' Caisley, both of Morpeth, Northumberland

Morpeth is a historic market town in Northumberland, North East England, lying on the River Wansbeck. Nearby towns include Ashington, Northumberland, Ashington and Bedlington, Northumberland, Bedlington. In the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 ...

. At the time of his marriage to Margaret in 1868, Charles was 45 and Margaret was 19. Emily was the third of four children born to the couple; her younger sister died of diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

in 1880 at the age of six. The marriage to Margaret was Charles's second; his first marriage produced nine children before the death of his wife in 1866.

The family moved to Sawbridgeworth

Sawbridgeworth is a town and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England, close to the border with Essex. It is east of Hertford and north of Epping. It is the northernmost part of the Greater London Built-up Area.

History

Prior to the Norman ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

, while Davison was still a baby; until the age of 11 she was educated at home. When her parents moved the family back to London she went to a day school, then spent a year studying in Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.Kensington High School and later won a

In July 1909 Davison was arrested with fellow suffragettes

In July 1909 Davison was arrested with fellow suffragettes  Davison developed the new tactic of setting fire to postboxes in December 1911. She was arrested for arson on the postbox outside parliament and admitted to setting fire to two others. Sentenced to six months in

Davison developed the new tactic of setting fire to postboxes in December 1911. She was arrested for arson on the postbox outside parliament and admitted to setting fire to two others. Sentenced to six months in

Bystanders rushed onto the track and attempted to aid Davison and Jones until both were taken to the nearby

Bystanders rushed onto the track and attempted to aid Davison and Jones until both were taken to the nearby

On 14 June 1913 Davison's body was transported from Epsom to London; her coffin was inscribed "Fight on. God will give the victory." Five thousand women formed a procession, followed by hundreds of male supporters, that took the body between

On 14 June 1913 Davison's body was transported from Epsom to London; her coffin was inscribed "Fight on. God will give the victory." Five thousand women formed a procession, followed by hundreds of male supporters, that took the body between

Davison's death marked a culmination and a turning point of the militant suffragette campaign. The

Davison's death marked a culmination and a turning point of the militant suffragette campaign. The

In 1968 a one-act play written by Joice Worters, ''Emily'', was staged in

In 1968 a one-act play written by Joice Worters, ''Emily'', was staged in

pdf version

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

An exhibit on Emily Davison, London School of Economics.

The original Pathé footage of Emily Davison running out of the crowds at the Derby

*

BBC profile

Archives of Emily Davison

at the

Library of the London School of Economics

"The Price of Liberty" manuscript (1913)

at

bursary

A bursary is a monetary award made by any educational institution or funding authority to individuals or groups. It is usually awarded to enable a student to attend school, university or college when they might not be able to, otherwise. Some awa ...

to Royal Holloway College

Royal Holloway, University of London (RHUL), formally incorporated as Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, is a public research university and a constituent college of the federal University of London. It has six schools, 21 academic departm ...

in 1891 to study literature. Her father died in early 1893 and she was forced to end her studies because her mother could not afford the fees of £20 a term.

On leaving Holloway, Davison became a live-in governess

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, th ...

, and continued studying in the evenings. She saved enough money to enrol at St Hugh's College, Oxford

St Hugh's College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford. It is located on a site on St Margaret's Road, to the north of the city centre. It was founded in 1886 by Elizabeth Wordsworth as a women's college, and accepte ...

, for one term to sit her finals

Final, Finals or The Final may refer to:

*Final (competition), the last or championship round of a sporting competition, match, game, or other contest which decides a winner for an event

** Another term for playoffs, describing a sequence of cont ...

; she achieved first-class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

in English, but could not graduate because degrees from Oxford were closed to women. She worked briefly at a church school

A Christian school is a school run on Christian principles or by a Christian organization.

The nature of Christian schools varies enormously from country to country, according to the religious, educational, and political cultures. In some countr ...

in Edgbaston

Edgbaston () is an affluent suburban area of central Birmingham, England, historically in Warwickshire, and curved around the southwest of the city centre.

In the 19th century, the area was under the control of the Gough-Calthorpe family an ...

between 1895 and 1896, but found it difficult and moved to Seabury, a private school

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

in Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Hov ...

, where she was more settled; she left the town in 1898 and became a private tutor and governess to a family in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It is ...

. In 1902 she began reading for a degree at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

; she graduated with third-class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

in 1908.

Activism

Davison joined theWomen's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

(WSPU) in November 1906. Formed in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

, the WSPU brought together those who thought that militant, confrontational tactics were needed to achieve their ultimate goal of women's suffrage. Davison joined in the WSPU's campaigning and became an officer of the organisation and a chief steward during marches. In 1908 or 1909 she left her job teaching and dedicated herself full-time to the union. She began taking increasingly confrontational actions, which prompted Sylvia Pankhurst

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (5 May 1882 – 27 September 1960) was a campaigning English feminist and socialist. Committed to organising working-class women in London's East End, and unwilling in 1914 to enter into a wartime political truce with ...

—the daughter of Emmeline and a full-time member of the WSPU—to describe her as "one of the most daring and reckless of the militants". In March 1909 she was arrested for the first time; she had been part of a deputation of 21 women who marched from Caxton Hall

Caxton Hall is a building on the corner of Caxton Street and Palmer Street, in Westminster, London, England. It is a Grade II listed building primarily noted for its historical associations. It hosted many mainstream and fringe political and art ...

to see the prime minister, H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

, the march ended in a fracas with police, and she was arrested for "assaulting the police in the execution of their duty". She was sentenced to a month in prison. After her release she wrote to ''Votes for Women'', the WSPU's newspaper, saying that "Through my humble work in this noblest of all causes I have come into a fullness of job and an interest in living which I never before experienced."

In July 1909 Davison was arrested with fellow suffragettes

In July 1909 Davison was arrested with fellow suffragettes Mary Leigh

Mary Leigh (née Brown; 1885–1978) was an English political activist and suffragette.

Life

Leigh was born as Mary or Marie Brown in 1885. She was born in Manchester and was a schoolteacher until her marriage to a builder, surnamed Leigh. She j ...

and Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

for interrupting a public meeting from which women were barred, held by the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

; she was sentenced to two months for obstruction. She went on hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

and was released after five and a half days, during which time she lost ; she stated that she "felt very weak" as a result. She was arrested again in September the same year for throwing stones to break windows at a political meeting; the assembly, which was to protest at the 1909 budget, was only open to men. She was sent to Strangeways prison

HM Prison Manchester is a Category A and B men's prison in Manchester, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. It is still commonly referred to as Strangeways, which was its former official name derived from the area in which it is ...

for two months. She again went on hunger strike and was released after two and a half days. She subsequently wrote to ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' to justify her action of throwing stones as one "which was meant as a warning to the general public of the personal risk they run in future if they go to Cabinet Ministers' meetings anywhere". She went on to write that this was justified because of the "unconstitutional action of Cabinet Ministers in addressing 'public meetings' from which a large section of the public is excluded".

Davison was arrested again in early October 1909, while preparing to throw a stone at the cabinet minister

A minister is a politician who heads a ministry, making and implementing decisions on policies in conjunction with the other ministers. In some jurisdictions the head of government is also a minister and is designated the ‘prime minister’, � ...

Sir Walter Runciman

Walter Runciman, 1st Baron Runciman (6 July 1847 – 13 August 1937) was an English and Scottish shipping magnate. He was born in the Scottish town of Dunbar.

He was the fourth son of Walter Runciman, master of a schooner and later a member o ...

; she acted in the mistaken belief the car in which he travelled contained Lloyd George. A suffragette colleague—Constance Lytton

Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton (12 February 1869 – 2 May 1923), usually known as Constance Lytton, was an influential British suffragette activist, writer, speaker and campaigner for prison reform, votes for women, and birth control. ...

—threw hers first, before the police managed to intervene. Davison was charged with attempted assault, but released; Lytton was imprisoned for a month. Davison used her court appearances to give speeches; excerpts and quotes from these were published in the newspapers. Two weeks later she threw stones at Runciman at a political meeting in Radcliffe, Greater Manchester

Radcliffe is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, Greater Manchester, England. It lies in the Irwell Valley north-northwest of Manchester and south-west of Bury and is contiguous with Whitefield to the south. The disused Manc ...

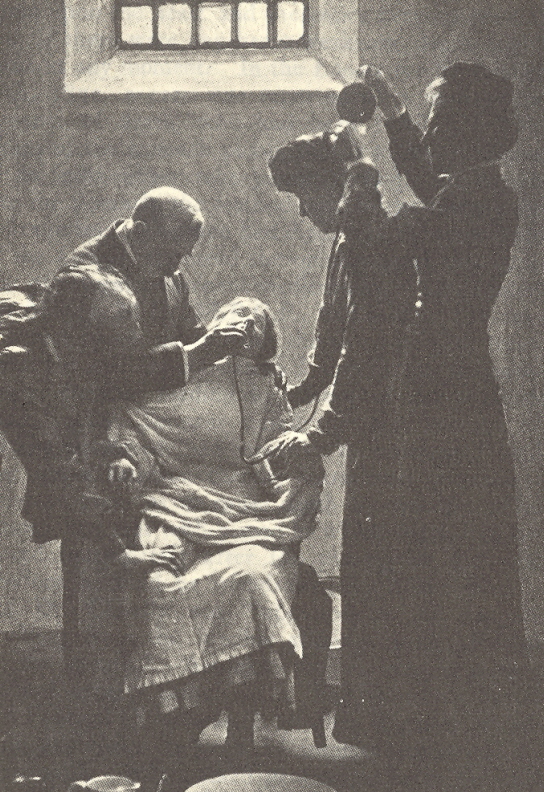

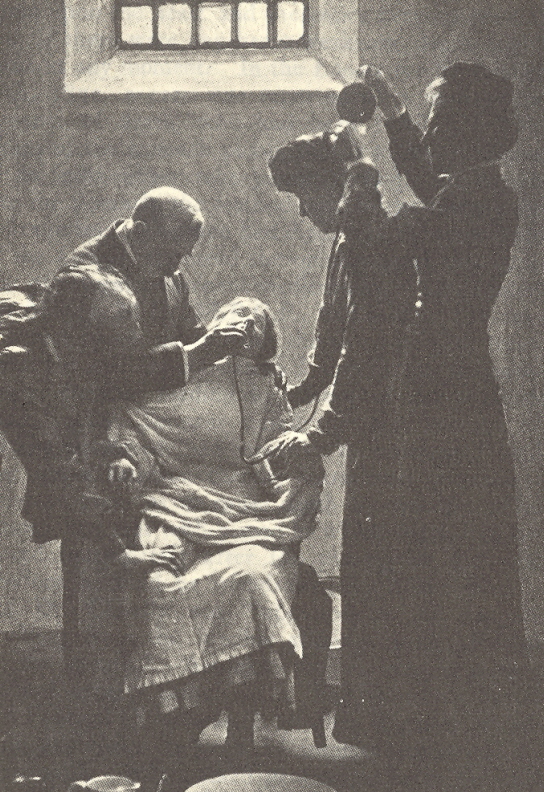

; she was arrested and sentenced to a week's hard labour. She again went on hunger strike, but the government had authorised the use of force-feeding

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into t ...

on prisoners. The historian Gay Gullickson describes the tactic as "extremely painful, psychologically harrowing, and raised the possibility of dying in jail from medical error or official misjudgment". Davison said that the experience "will haunt me with its horror all my life, and is almost indescribable. ... The torture was barbaric". Following the first episode of forced feeding, and to prevent a repeat of the experience, Davison barricaded herself in her cell using her bed and a stool and refused to allow the prison authorities to enter. They broke one of the window panes to the cell and turned a fire hose on her for 15 minutes, while attempting to force the door open. By the time the door was opened, the cell was six inches deep in water. She was taken to the prison hospital where she was warmed with hot water bottles. She was force-fed shortly afterwards and released after eight days. Davison's treatment prompted the Labour Party MP Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

to ask a question in the House of Commons about the "assault committed on a woman prisoner in Strangeways"; Davison sued the prison authorities for the use of the hose and, in January 1910, she was awarded 40 shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence or ...

in damages.

In April 1910 Davison decided to gain entry to the floor of the House of Commons to ask Asquith about the vote for women. She entered the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

with other members of the public and made her way into the heating system, where she hid overnight. On a trip from her hiding place to find water, she was arrested by a policeman, but not prosecuted. The same month she became an employee of the WSPU and began to write for ''Votes for Women''.

A bipartisan group of MPs formed a Conciliation Committee in early 1910 and proposed a Conciliation Bill

Conciliation bills were proposed legislation which would extend the right of women to vote in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland to just over a million wealthy, property-owning women. After the January 1910 election, an all-party Con ...

that would have brought the vote to a million women, so long as they owned property. While the bill was being discussed, the WSPU put in a temporary truce on activity. The bill failed that November when Asquith's Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

government reneged on a promise to allow parliamentary time to debate the bill. A WSPU delegation of around 300 women tried to present him with a petition, but were prevented from doing so by an aggressive police response; the suffragettes, who called the day Black Friday, complained of assault, much of which was sexual in nature. Davison was not one of the 122 people arrested, but was incensed by the treatment of the delegation; the following day she broke several windows in the Crown Office

The Crown Office, also known (especially in official papers) as the Crown Office in Chancery, is a section of the Ministry of Justice (formerly the Lord Chancellor's Department). It has custody of the Great Seal of the Realm, and has certain ad ...

in parliament. She was arrested and sentenced to a month in prison. She went on hunger strike again and was force-fed for eight days before being released.

On the night of the 1911 census, 2 April, Davison hid in a cupboard in St Mary Undercroft

The Chapel of St Mary Undercroft is a Church of England chapel located in the Palace of Westminster, London, England. The chapel is accessed via a flight of stairs in the south east corner of Westminster Hall.

It had been a crypt below St Steph ...

, the chapel of the Palace of Westminster. She remained hidden overnight to avoid being entered onto the census; the attempt was part of a wider suffragette action to avoid being listed by the state. She was found by a cleaner, who reported her presence; Davison was arrested but not charged. The Clerk of Works at the House of Commons completed a census form to include Davison in the returns. She was included in the census twice, as her landlady also included her as being present at her lodgings. Davison had continually written letters to the press to put forward the WSPU position in a non-violent manner—she had 12 published in ''The Manchester Guardian'' between 1909 and 1911—and she undertook a campaign between 1911 and 1913 during which she wrote nearly 200 letters to over 50 newspapers. Several of her letters were published, including about 26 in ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' between September 1910 and 1912.

Davison developed the new tactic of setting fire to postboxes in December 1911. She was arrested for arson on the postbox outside parliament and admitted to setting fire to two others. Sentenced to six months in

Davison developed the new tactic of setting fire to postboxes in December 1911. She was arrested for arson on the postbox outside parliament and admitted to setting fire to two others. Sentenced to six months in Holloway Prison

HM Prison Holloway was a closed category prison for adult women and young offenders in Holloway, London, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. It was the largest women's prison in western Europe, until its closure in 2016.

Hist ...

, she did not go on hunger strike at first, but the authorities required that she be force-fed between 29 February and 7 March 1912 because they considered her health and appetite to be in decline. In June she and other suffragette inmates barricaded themselves in their cells and went on hunger strike; the authorities broke down the cell doors and force-fed the strikers. Following the force-feeding, Davison decided on what she described as a "desperate protest ... made to put a stop to the hideous torture, which was now our lot" and jumped from one of the interior balconies of the prison. She later wrote:

... as soon as I got out I climbed on to the railing and threw myself out to the wire-netting, a distance of between 20 and 30 feet. The idea in my mind was "one big tragedy may save many others". I realised that my best means of carrying out my purpose was the iron staircase. When a good moment came, quite deliberately I walked upstairs and threw myself from the top, as I meant, on to the iron staircase. If I had been successful I should undoubtedly have been killed, as it was a clear drop of 30 to 40 feet. But I caught on the edge of the netting. I then threw myself forward on my head with all my might.She cracked two

vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic i ...

and badly injured her head. Shortly afterwards, and despite her injuries, she was again force-fed before being released ten days early. She wrote to ''The Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed int ...

'' to explain why she "attempted to commit suicide":

I did it deliberately and with all my power, because I felt that by nothing but the sacrifice of human life would the nation be brought to realise the horrible torture our women face! If I had succeeded I am sure that forcible feeding could not in all conscience have been resorted to again.As a result of her action Davison suffered discomfort for the rest of her life. Her arson of postboxes was not authorised by the WSPU leadership and this, together with her other actions, led to her falling out of favour with the organisation; Sylvia Pankhurst later wrote that the WSPU leadership wanted "to discourage ...

avison Avison is a name. Notable people with that name include:

; As a surname

* Al Avison (192084), American comic book artist

*Charles Avison (170970), English composer during the Baroque and Classical periods

* David Avison (19372004), American photogr ...

in such tendencies ... She was condemned and ostracized as a self-willed person who persisted in acting upon her own initiative without waiting for official instructions." A statement Davison wrote on her release from prison for ''The Suffragette''—the second official newspaper of the WSPU—was published by the union after her death.

Davison spent some time on her release being cared for by Minnie Turner in Brighton before going up north to her mother in Northumberland.

In November 1912 Davison was arrested for a final time, for attacking a Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

minister with a horsewhip; she had mistaken the man for Lloyd George. She was sentenced to ten days' imprisonment and released early following a four-day hunger strike. It was the seventh time she had been on hunger strike, and the forty-ninth time she had been force-fed.

Fatal injury at the Derby

On 4 June 1913 Davison obtained two flags bearing the suffragette colours of purple, white and green from the WSPU offices; she then travelled by train toEpsom

Epsom is the principal town of the Borough of Epsom and Ewell in Surrey, England, about south of central London. The town is first recorded as ''Ebesham'' in the 10th century and its name probably derives from that of a Saxon landowner. The ...

, Surrey, to attend the Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

. She positioned herself in the infield

Infield is a sports term whose definition depends on the sport in whose context it is used.

Baseball

In baseball, the diamond, as well as the area immediately beyond it, has both grass and dirt, in contrast to the more distant, usually grass-c ...

at Tattenham Corner, the final bend before the home straight

{{about, the element of a track, , Straight (disambiguation)

In many forms of racing, a straight or stretch is a part of the race track in which the competitors travel in a straight line for any significant time, as opposed to a bend or curve. The ...

. At this point in the race, with some of the horses having passed her, she ducked under the guard rail and ran onto the course; she may have held in her hands one of the suffragette flags. She reached up to the reins of Anmer—King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

's horse, ridden by Herbert Jones—and was hit by the animal, which would have been travelling at around per hour, four seconds after stepping onto the course. Anmer fell in the collision and partly rolled over his jockey, who had his foot momentarily caught in the stirrup. Davison was knocked to the ground unconscious; some reports say she was kicked in the head by Anmer, but the surgeon who operated on Davison stated that "I could find no trace of her having been kicked by a horse". The event was captured on three news cameras.

Bystanders rushed onto the track and attempted to aid Davison and Jones until both were taken to the nearby

Bystanders rushed onto the track and attempted to aid Davison and Jones until both were taken to the nearby Epsom Cottage Hospital

Epsom and Ewell Cottage Hospital is a small hospital in West Park Road, Horton Lane, Epsom, Surrey. It is managed by CSH Surrey.

History

The hospital has its origins in a facility established at Pembroke Cottages at Pikes Hill in April 1873. It m ...

. Davison was operated on two days later, but she never regained consciousness; while in hospital she received hate mail. She died on 8 June, aged 40, from a fracture at the base of her skull. Found in Davison's effects were the two suffragette flags, the return stub of her railway ticket to London, her race card, a ticket to a suffragette dance later that day and a diary with appointments for the following week. The King and Queen Mary were present at the race and made enquiries about the health of both Jones and Davison. The King later recorded in his diary that it was "a most regrettable and scandalous proceeding"; in her journal the Queen described Davison as a "horrid woman". Jones suffered a concussion and other injuries; he spent the evening of 4 June in London, before returning home the following day. He could recall little of the event: "She seemed to clutch at my horse, and I felt it strike her." He recovered sufficiently to race Anmer at Ascot Racecourse

Ascot Racecourse ("ascot" pronounced , often pronounced ) is a dual-purpose British racecourse, located in Ascot, Berkshire, England, which is used for thoroughbred horse racing. It hosts 13 of Britain's 36 annual Flat Group 1 horse races and ...

two weeks later.

The inquest into Davison's death took place at Epsom on 10 June; Jones was not well enough to attend. Davison's half-brother, Captain Henry Davison, gave evidence about his sister, saying that she was "a woman of very strong reasoning faculties, and passionately devoted to the women's movement". The coroner decided that, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, Davison had not committed suicide. The coroner also decided that, although she had waited until she could see the horses, "from the evidence it was clear that the woman did not make for His Majesty's horse in particular". The verdict of the court was:

that Miss Emily Wilding Davison died of fracture of the base of the skull, caused by being accidentally knocked down by a horse through wilfully rushing on to the racecourse on Epsom Downs during the progress of the race for the Derby; death was due to misadventure.Davison's purpose in attending the Derby and walking onto the course is unclear. She did not discuss her plans with anyone or leave a note. Several theories have been suggested, including that she intended to cross the track, believing that all horses had passed; that she wanted to pull down the King's horse; that she was trying to attach one of the WSPU flags to a horse; or that she intended to throw herself in front of one of the horses. The historian Elizabeth Crawford considers that "subsequent explanations of ... avison'saction have created a tangle of fictions, false deductions, hearsay, conjecture, misrepresentation and theory". In 2013 a

Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned enterprise, state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a four ...

documentary used forensic examiners who digitised the original nitrate film

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

from the three cameras present. The film was digitally cleaned and examined. Their examination suggests that Davison intended to throw a suffragette flag around the neck of a horse or attach it to the horse's bridle

A bridle is a piece of equipment used to direct a horse. As defined in the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', the "bridle" includes both the that holds a bit that goes in the mouth of a horse, and the reins that are attached to the bit.

Headgear w ...

. A flag was gathered from the course; this was put up for auction and, as at 2021, it hangs in the Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank ...

. Michael Tanner, the horse-racing historian and author of a history of the 1913 Derby, doubts the authenticity of the item. Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, and ...

, the auction house that sold it, describe it as a sash that was "reputed" to have been worn by Davison. The seller stated that her father, Richard Pittway Burton, was the Clerk of the Course at Epsom; Tanner's search of records shows Burton was listed as a dock labourer two weeks prior to the Derby. The official Clerk of the Course on the day of the Derby was Henry Mayson Dorling. When the police listed Davison's possessions, they itemised the two flags provided by the WSPU, both folded up and pinned to the inside of her jacket. They measured 44.5 by 27 inches (113 × 69 cm); the sash displayed at the Houses of Parliament measures 82 by 12 inches (210 × 30 cm).

Tanner considers that Davison's choice of the King's horse was "pure happenstance", as her position on the corner would have left her with a limited view. Examination of the newsreels by the forensic team employed by the Channel 4 documentary determined that Davison was closer to the start of the bend than had been previously assumed, and would have had a better view of the oncoming horses.

The contemporary news media were largely unsympathetic to Davison, and many publications "questioned her sanity and characterised her actions as suicidal". ''The Pall Mall Gazette'' said it had "pity for the dementia which led an unfortunate woman to seek a grotesque and meaningless kind of 'martyrdom' ", while ''The Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet i ...

'' described Davison as "A well-known malignant suffragette, ... hohas a long record of convictions for complicity in suffragette outrages." The journalist for ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' observed that "Deep in the hearts of every onlooker was a feeling of fierce resentment with the miserable woman"; the unnamed writer in ''The Daily Mirror

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'' opined that "It was quite evident that her condition was serious; otherwise many of the crowd would have fulfilled their evident desire to lynch her."

The WSPU were quick to describe her as a martyr, part of a campaign to identify her as such. ''The Suffragette'' newspaper marked Davison's death by issuing a copy showing a female angel with raised arms standing in front of the guard rail of a racecourse. The paper's editorial stated that "Davison has proved that there are in the twentieth-century people who are willing to lay down their lives for an ideal". Religious phraseology was used in the issue to describe her act, including "Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends", which Gullickson reports as being repeated several times in subsequent discussions of the events. A year after the Derby, ''The Suffragette'' included "The Price of Liberty", an essay by Davison. In it, she had written "To lay down life for friends, that is glorious, selfless, inspiring! But to re-enact the tragedy of Calvary for generations yet unborn, that is the last consummate sacrifice of the Militant".

Funeral

On 14 June 1913 Davison's body was transported from Epsom to London; her coffin was inscribed "Fight on. God will give the victory." Five thousand women formed a procession, followed by hundreds of male supporters, that took the body between

On 14 June 1913 Davison's body was transported from Epsom to London; her coffin was inscribed "Fight on. God will give the victory." Five thousand women formed a procession, followed by hundreds of male supporters, that took the body between Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

and Kings Cross stations; the procession stopped at St George's, Bloomsbury

St George's, Bloomsbury, is a parish church in Bloomsbury, London Borough of Camden, United Kingdom. It was designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor and consecrated in 1730. The church crypt houses the Museum of Comedy.

History

The Commissioners for the ...

for a brief service led by its vicar, Charles Baumgarten, and Claude Hinscliff

Reverend Claude Hinscliff (1875–1964) was a British suffragist.

Education and early career

Hinscliff studied for his licentiate in theology at Durham University. He matriculated in 1893 and was awarded a scholarship after performing well in t ...

, who were members of the Church League for Women's Suffrage

The Church League for Women's Suffrage (CLWS) was an organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom.

The league was started in London, but by 1913 it had branches across England, in Wales and Scotland and Ireland.

Aims an ...

. The women marched in ranks wearing the suffragette colours of white and purple, which ''The Manchester Guardian'' described as having "something of the deliberate brilliance of a military funeral"; 50,000 people lined the route. The event, which was organised by Grace Roe

Eleanor Grace Watney Roe (1885–1979) was Head of Suffragette operations for the Women's Social and Political Union. She was released from prison after the outbreak of World War I due to an amnesty for suffragettes negotiated with the governme ...

, is described by June Purvis

June Purvis is an emeritus professor of women's and gender history at the University of Portsmouth.

From 2014-18, Purvis was Chair of the Women’s History Network UK and from 2015-20 Treasurer of the International Federation for Research in Wo ...

, Davison's biographer, as "the last of the great suffragette spectacles". Emmeline Pankhurst planned to be part of the procession, but she was arrested on the morning, ostensibly to be returned to prison under the "Cat and Mouse" Act (1913).

The coffin was taken by train to Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

with a suffragette guard of honour for the journey; crowds met the train at its scheduled stops. The coffin remained overnight at the city's central station

Central stations or central railway stations emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century as railway stations that had initially been built on the edge of city centres were enveloped by urban expansion and became an integral part of the ...

before being taken to Morpeth. A procession of about a hundred suffragettes accompanied the coffin from the station to the St. Mary the Virgin church; it was watched by thousands. Only a few of the suffragettes entered the churchyard, as the service and interment were private. Her gravestone bears the WSPU slogan "Deeds not words".

Approach and analysis

Davison's death marked a culmination and a turning point of the militant suffragette campaign. The

Davison's death marked a culmination and a turning point of the militant suffragette campaign. The First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

broke out the following year and, on 10 August 1914, the government released all women hunger strikers and declared an amnesty. Emmeline Pankhurst suspended WSPU operations on 13 August. Pankhurst subsequently assisted the government in the recruitment of women for war work. In 1918 Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act 1918

The Representation of the People Act 1918 was an Act of Parliament passed to reform the electoral system in Great Britain and Ireland. It is sometimes known as the Fourth Reform Act. The Act extended the franchise in parliamentary elections, also ...

. Among the changes was the granting of the vote to women over the age of 30 who could pass property qualifications. The legislation added 8.5 million women to the electoral roll; they constituted 43% of the electorate. In 1928 the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act lowered the voting age for women to 21 to put them on equal terms with male voters.

Crawford sees the events at the 1913 Derby as a lens "through which ... avison'swhole life has been interpreted", and the uncertainty of her motives and intentions that day has affected how she has been judged by history. Carolyn Collette, a literary critic who has studied Davison's writing, identifies the different motives ascribed to Davison, including "uncontrolled impulses" or a search for martyrdom for women's suffrage. Collette also sees a more current trend among historians "to accept what some of her close contemporaries believed: that Davison's actions that day were deliberate" and that she attempted to attach the suffragette colours to the King's horse. Cicely Hale

Cicely Bertha Hale (5 September 1884 – June 1981) was an English suffragette, health visitor, and author. In 1908, having been inspired by hearing Christabel Pankhurst and Emmeline Pankhurst speak, she became an assistant to Mary Howe in the ...

, a suffragette who worked at the WSPU and who knew Davison, described her as "a fanatic" who was prepared to die but did not mean to. Other observers, such as Purvis, and Ann Morley and Liz Stanley—Davison's biographers—agree that Davison did not mean to die.

Davison was a staunch feminist and a passionate Christian whose outlook "invoked both medieval history and faith in God as part of the armour of her militancy". Her love of English literature, which she had studied at Oxford, was shown in her identification with Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

's ''The Knight's Tale

"The Knight's Tale" ( enm, The Knightes Tale) is the first tale from Geoffrey Chaucer's '' The Canterbury Tales''.

The Knight is described by Chaucer in the "General Prologue" as the person of highest social standing amongst the pilgrims, t ...

'', including being nicknamed "Faire Emelye". Much of Davison's writing reflected the doctrine of the Christian faith and referred to martyrs, martyrdom and triumphant suffering; according to Collette, the use of Christian and medieval language and imagery "directly reflects the politics and rhetoric of the militant suffrage movement". Purvis writes that Davison's committed Anglicanism would have stopped her from committing suicide because it would have meant that she could not be buried in consecrated ground

In Christian countries a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster-Scots, this can also ...

. Davison wrote in "The Price of Liberty" about the high cost of devotion to the cause:

In the New Testament, the Master reminded His followers that when the merchant had found the Pearl of Great Price, he sold all that he had in order to buy it. That is the parable of Militancy! It is that which the women warriors are doing to-day.Davison held a firm moral conviction that

Some are truer warriors than others, but the perfect Amazon is she who will sacrifice all even unto the last, to win the Pearl of Freedom for her sex.

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

was a moral and political force for good. She attended the annual May Day rallies in Hyde Park and, according to the historian Krista Cowman, "directly linked her militant suffrage activities with socialism". Her London and Morpeth funeral processions contained a heavy socialist presence in appreciation of her support for the cause.

Legacy

In 1968 a one-act play written by Joice Worters, ''Emily'', was staged in

In 1968 a one-act play written by Joice Worters, ''Emily'', was staged in Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

, focusing on the use of violence against the women's campaign. Davison is the subject of an opera, ''Emily'' (2013), by the British composer Tim Benjamin, and of "Emily Davison", a song by the American rock singer Greg Kihn

Gregory Stanley Kihn (born July 10, 1949) is an American rock musician, radio personality, and novelist. He founded and led The Greg Kihn Band, which scored hit songs in the 1980s, and has written several horror novels.

History

Kihn was born ...

. Davison also appears as a supporting character in the 2015 film ''Suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

'', in which she is portrayed by Natalie Press

Natalie Press (born 15 August 1980) is an English actress. She is known for her performance in the 2004 film ''My Summer of Love'' and a number of short and feature-length Independent film, independent films, including ''Wasp (2003 film), Wasp' ...

. Her death and funeral form the climax of the film. In January 2018 the cantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

The meaning of ...

''Pearl of Freedom'', telling the story of Davison's suffragette struggles, was premiered. The music was by the composer Joanna Marsh; the librettist

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major litu ...

was David Pountney

Sir David Willoughby Pountney (born 10 September 1947) is a British-Polish theatre and opera director and librettist internationally known for his productions of rarely performed operas and new productions of classic works. He has directed over ...

.

In 1990 the Labour MPs Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British politician, writer and diarist who served as a Cabinet of the United Kingdom, Cabinet minister in the 1960s and 1970s. ...

and Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the political left of the Labour Party, Corbyn describes himself as a socialist ...

placed a commemorative plaque inside the cupboard in which Davison had hidden eighty years earlier. In April 2013 a plaque was unveiled at Epsom racecourse

Epsom Downs is a Grade 1 racecourse on the hills associated with Epsom in Surrey, England which is used for thoroughbred horse racing. The "Downs" referred to in the name are part of the North Downs.

The course, which has a crowd capacity of 13 ...

to mark the centenary of her death. In January 2017 Royal Holloway announced that its new library would be named after her. The statue of Millicent Fawcett

The statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, honours the British suffragist leader and social campaigner Dame Millicent Fawcett. It was made in 2018 by Gillian Wearing. Following a campaign and petition by the activist Caroline C ...

in Parliament Square

Parliament Square is a square at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London. Laid out in the 19th century, it features a large open green area in the centre with trees to its west, and it contai ...

, London, unveiled in April 2018, features Davison's name and picture, along with those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters, on the plinth

A pedestal (from French ''piédestal'', Italian ''piedistallo'' 'foot of a stall') or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In c ...

of the statue. The Women's Library

The Women's Library is England's main library and museum resource on women and the women's movement, concentrating on Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries. It has an institutional history as a coherent collection dating back to the mid-1920s, ...

, at the London School of Economics

, mottoeng = To understand the causes of things

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £240.8 million (2021)

, budget = £391.1 millio ...

, holds several collections related to Davison. They include her personal papers and objects connected to her death.

A statue of Davison, by the artist Christine Charlesworth, was installed in the marketplace at Epsom in 2021, following a campaign by volunteers from the Emily Davison Memorial Project.

See also

*List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the public ...

* Timeline of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant ...

* Women's suffrage organisations

Notes and references

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Cited page numbers from thpdf version

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

An exhibit on Emily Davison, London School of Economics.

The original Pathé footage of Emily Davison running out of the crowds at the Derby

*

BBC profile

Archives of Emily Davison

at the

Women's Library

The Women's Library is England's main library and museum resource on women and the women's movement, concentrating on Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries. It has an institutional history as a coherent collection dating back to the mid-1920s, ...

at thLibrary of the London School of Economics

"The Price of Liberty" manuscript (1913)

at

Google Arts & Culture

Google Arts & Culture (formerly Google Art Project) is an online platform of high-resolution images and videos of artworks and cultural artifacts from partner cultural organizations throughout the world.

It utilizes high-resolution image technol ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Davison, Emily

1872 births

1913 deaths

Alumni of Royal Holloway, University of London

Alumni of St Hugh's College, Oxford

British feminists

British women activists

Burials in Northumberland

Deaths by horse-riding accident in England

English Christians

English suffragettes

Holloway brooch recipients

Hunger Strike Medal recipients

People from Blackheath, London

Schoolteachers from London

English socialist feminists

Women of the Victorian era